Key Takeaways

- CLTs provide regular income to charities and, later on, assets to heirs.

- Potential benefits include tax deductions and family legacy.

- Potential risks include irrevocability and interest rate sensitivity.

If you’re like many investors with significant assets, you may feel you’re in a kind of tug-of-war between two financial goals:

- Leaving money to your heirs

- Benefiting organizations that are meaningful to you and that help people who need it

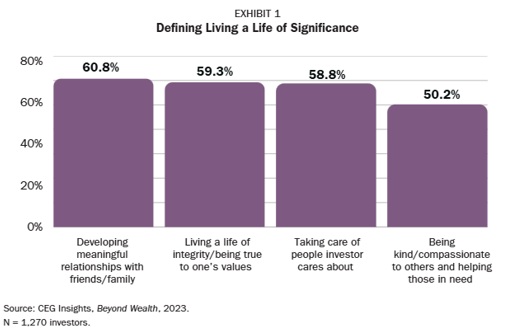

Indeed, CEG Insights research found that “taking care of people (the) investor cares about” was how nearly 60% of investors defined living a life of significance—while 50% defined it as “being kind/compassionate to others and helping those in need.” (See Exhibit 1.)

The good news: There are philanthropic tools that can potentially help you strike the right balance for you between those two objectives. One such tool is called a charitable lead trust, or CLT—and it may enable you to have a positive impact on both your family and your favorite causes.

Here’s an overview that spells out the ABCs of CLTs, and how to decide whether this powerful approach to charitable planning could be an option worth exploring further.

The basics

The basic mechanics of a charitable lead trust are well established:

- Establish a charitable lead trust and fund it. You can establish a charitable lead trust while alive or through your estate plan. To fund it, you contribute assets (cash or publicly traded securities are common candidates) to the trust, which invests and manages those assets.

- The trust sends payments to one or more charities. The trust provides an annual income payment to a chosen charity (or charities, as the case may be). These charitable payments can go on for a fixed number of years or for the lifespan of an individual. There is no required minimum (or maximum) payment to the charity, as long as a payment is made annually.

- The remaining assets are distributed to you or your loved ones. At the end of the charitable trust term, the remaining assets are distributed to non-charity beneficiaries. Often that means your loved ones (usually those who are of your same generation or the next generation, in order to avoid the generation-skipping tax). Ideally, the trust assets have grown over time—leaving a nice amount of wealth left over. That said, you can also structure a CLT so that the remaining assets revert to you.

Beyond the basics

That said, as with most trusts, CLTs have additional complexities and rules that you need to understand and follow.

Perhaps the most important trait of a CLT is that it’s an irrevocable trust. That means once you put assets into one, you cannot change your mind later and pull them out. The upshot: Charitable intent is key. You probably don’t want to even think about creating and funding a CLT unless you’re certain you want some of your wealth to go to one or more charities.

If you are willing to fund this type of irrevocable trust, however, you have the potential to receive certain tax benefits. For example:

- Tax-deferred growth. The assets in the CLT can be structured to grow tax-deferred, if you utilize proper planning and appropriate investment vehicles. (More on this later.)

- Tax deduction. When you create and fund the CLT, you may get an income tax deduction. There are different tax deductions depending on factors such as the assets being used, the projected payments to charity, the terms of the trust, and the IRS interest rate that forms the basis of the anticipated growth of the assets in the trust.

CLATs, CLUTs and other flavors of CLTs

It’s also important to recognize that CLTs aren’t a monolithic giving vehicle—they offer some flexibility for would-be charitable donors.

For example, a CLT can be established as either a charitable lead annuity trust (CLAT) or a charitable lead unitrust (CLUT). With a CLAT, the charity gets a specific, consistent amount of money each year—the annual payment doesn’t fluctuate. With a CLUT, by contrast, the charity receives a specific, consistent percentage of the trust’s assets valued annually—meaning the exact amount of money paid to the charity can rise or fall from year to year.

In addition, there are two overall types of CLTs—grantor and non-grantor—that differ in ways that can impact tax-related issues.

- Grantor CLTs allow the grantor to take an immediate income tax charitable deduction. However, the grantor will have to pay taxes on the trust’s income throughout the trust’s term—effectively eroding some of that up-front deduction over time.

- Non-grantor CLTs are set up so the trust itself—not the grantor—is considered the owner of the assets. Therefore, the grantor doesn’t get an immediate tax deduction when gifting assets to the trust—and it’s the trust that pays the taxes on the income generated. Additionally, the trust is eligible to claim an unlimited income tax deduction for the distributions of funds to the charity.

Benefits and risks

Despite the complexities involved in navigating the world of CLTs, these trusts are seen as beneficial by many individuals and charitable organizations for reasons that include:

- Regular income and meaningful giving. Charities like CLTs because the trusts can potentially enable them to receive a steady stream of income annually, helping them with planning around their mission and purpose. Charitable donors like CLTs because they can gift large sums of money at once rather than send funds in smaller amounts over time.

- Possible tax advantages. As noted, depending on several factors, donors may be able to receive an immediate tax deduction—which may be particularly advantageous if the donor generated a much larger than usual amount of income in a particular year.

- Family financial benefits. A CLT can ensure that your chosen heirs receive some of your wealth without incurring estate taxes. And if the assets in the trust grow tax-deferred, your heirs could benefit by receiving more wealth than they may have otherwise.

But keep in mind that CLTs come with risks and issues that need to be weighed carefully when deciding whether to use this type of trust. Some of the risks that need to be on your radar screen include:

- They’re irrevocable. As noted, once you place assets in a CLT, you can’t change your mind and pull them back out. That means assets that go to a CLT should be those you want to provide a benefit to a charity.

- The value can fluctuate. Because the assets in a CLT are invested, they can fall in value as well as rise. There’s no guarantee that your heirs will ultimately receive the amount of wealth you hoped they would when setting up the trust.

- They’re sensitive to interest rates. Often, CLTs are viewed as better options when interest rates are relatively low. That’s because the IRS applies a discount rate to CLTs, known as the 7520 rate, that rises and falls along with overall interest rates. If assets in the CLT outperform the 7520 rate, the excess earnings will pass to the non-charity beneficiaries free of transfer tax. The higher the rate, the more difficult it is to achieve such outperformance—and the greater the risk that there will be a smaller amount of excess earnings to pass on.

Next steps

Charitable trusts are usually complicated and subject to specific IRS rules, so anyone considering establishing a charitable trust, including a charitable lead trust, should consult with their legal or tax advisor. If you are considering making charitable giving part of your wealth plan, you’ll want to talk with the financial professionals with whom you work to determine the best vehicle and strategy for your situation. You also should consider discussing your goals with your family.

VFO Inner Circle Special Report

By John J. Bowen Jr.

© Copyright 2025 by AES Nation, LLC. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means, including but not limited to electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or any information storage retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Unauthorized copying may subject violators to criminal penalties as well as liabilities for substantial monetary damages up to $100,000 per infringement, costs and attorneys’ fees.

This publication should not be utilized as a substitute for professional advice in specific situations. If legal, medical, accounting, financial, consulting, coaching or other professional advice is required, the services of the appropriate professional should be sought. Neither the author nor the publisher may be held liable in any way for any interpretation or use of the information in this publication.

The author will make recommendations for solutions for you to explore that are not his own. Any recommendation is always based on the author’s research and experience.

The information contained herein is accurate to the best of the publisher’s and author’s knowledge; however, the publisher and author can accept no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information or for loss or damage caused by any use thereof.

Nathan Brinkman is a registered representative and offers securities and investment advisory services through MML Investors Services, LLC. Member SIPC (www.sipc.org) Supervisory office: 8888 Keystone Crossing #1600, Indianapolis, IN 46240 (317) 469-9999. Triumph Wealth Management, LLC is not a subsidiary or affiliate of MML Investors Services, LLC or its affiliated companies. Nathan Brinkman: CA Insurance License #0C27168 CRN202812-10034497